How Far Can I Push a GenServer?

I’ve been using Elixir for a while and I’ve implemented a number of GenServers. But while I think I mostly understand the purpose of them, I’ve not gotten the chance to push one it’s limits, scale it up, and find ways to address it’s bottlenecks. I thought that it would be fun to create something to which I could give the URL as part of a presentation and have some confidence that it would be able to handle all the users who connected to it. So recently I implemented a simple game grid using Phoenix LiveView and emojis as indicators of player and objects. If you would like to learn about my journey, read on! But note that you’ll probably want to have at least a basic understanding of GenServers first. You might start by reading this and/or watching this.

If you would like to look at the source code for this project you can see it on GitHub.

TL;DR: This post isn’t very TL;DR-able 😁 I don’t have any conclusions or recommendations to share, just a journey. I invite you to join me to learn what I’ve learned!

Overview of the Project

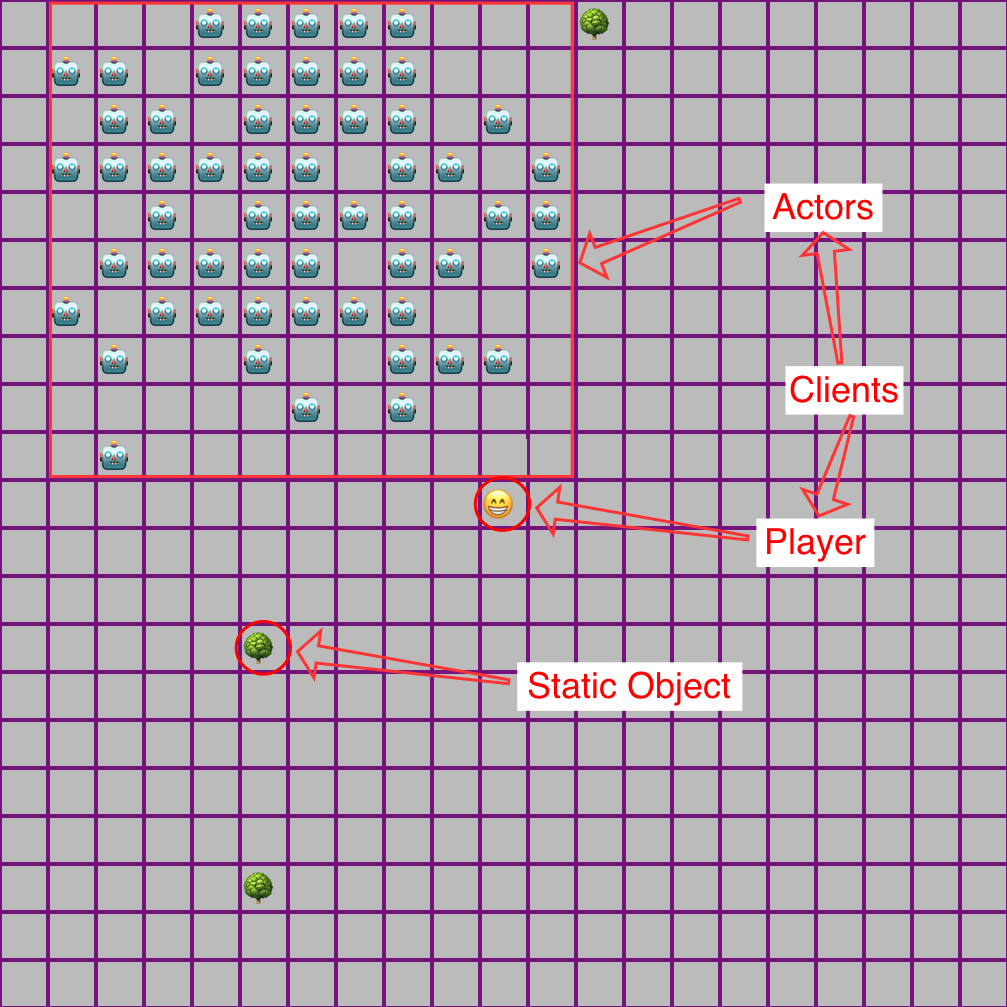

It is an Elixir Phoenix app which starts up a GenServer process as the game server which:

- Keeps track of a 1000x1000 square game grid, populated with random objects (trees, to start)

- Allows clients (other Elixir processes, players + actors) to make moves

- Keeps track of the current position of clients, indexed by their process ID (PID)

There will then also be two kinds of “client”s of the game server:

- A LiveView UI which handle the player’s session and key presses

- A set of

GenServers (the “actors”) which will move randomly every second.

The move Message

To implement moves I started out with a simple move message. Clients can send this message to the game server with their new position. An LiveView process sends this once at startup to establish a starting position and then again each time the player presses an arrow key. An actor processes simply sends a move message once every second to move randomly.

The move message itself worked fine, but a player wouldn’t see any movement from actor processes until they (the player) moved. I dealt with this problem later, so see the “Sending Map Updates Asyncronously” section below for my solution.

Linking Clients

One thing that I discovered early on was that the game would sometimes crash and the player would end up with a extra “dead” copy of themself on the board. It turns out that this would happen whenever the player pressed any non-arrow key (including modifier keys like alt/option). This is because I was handling key presses with a case statement without accounting for anything other than the four arrow keys. When another key was pressed a CaseClauseError error would be raised and crash the LiveView process. LiveView handled this great by automagically creating a new process for the session, but my game server would still think that the old process was around and thus the old avatar was still there. My fix: the game server calls Process.link to link itself to each client and then traps exits to clean up the information it has about that client’s PID.

Nitty-gritty detail

I initially called Process.link whenever a client sent a move message. The documentation says “If such a link exists already, this function does nothing”, so it wasn’t a problem. But the more elegant way would be to just do it once.

Also: I started with handle_cast, but it doesn’t give you a PID. So I couldn’t just have clients send a move without getting a response because the game server needs to track clients by their PID. So I used handle_call, but that will probably be needed in the long run anyway since clients will eventually need feedback to know if their moves are invalid (i.e. something is there which can’t occupy the same space at the same time)

Registering

I was beginning to have various reasons for thinking I should create a new kind of message that clients send to the game server to register themselves:

Process.linkcould be called only once once- It would simplify the code to handle

movemessages (no need to check if the PID already exsits) - It would allow for the game server to send the map section right away

It will also later turn out to be a useful opportunity for the client to send configuration options to the server (keep reading for more!)

Measuring

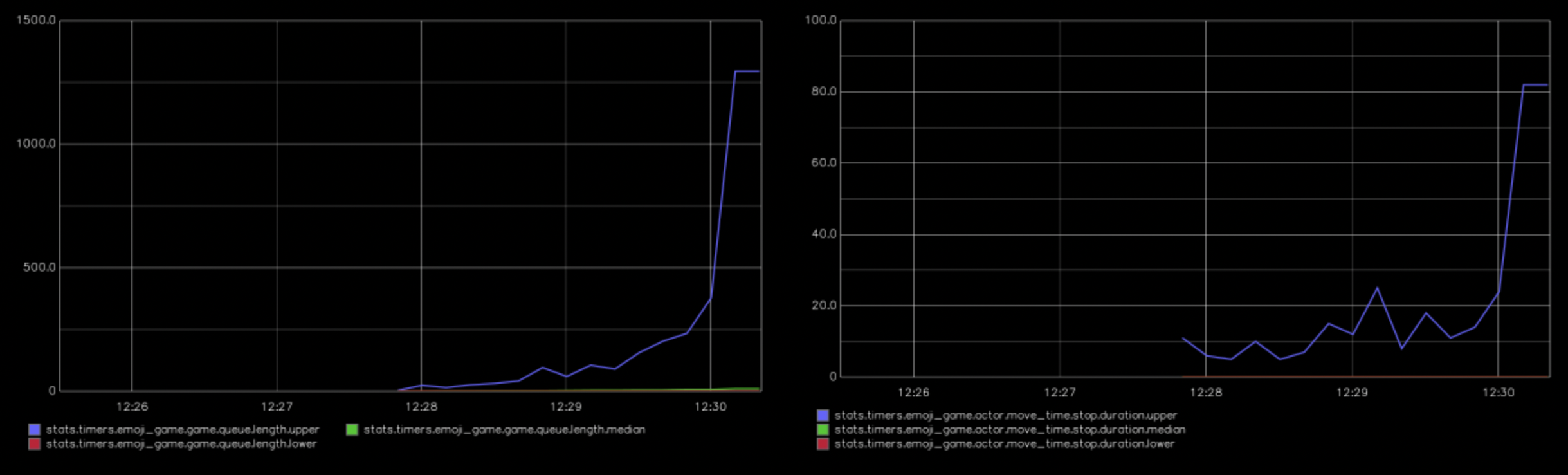

With that done I wanted to optimize the process so that I could handle more clients. But, before optimizing my code, I wanted to add some metrics tracking because you can’t optimize what you can’t see! Thanks to telemetry being included with Phoenix I was able to quickly add metrics for the game server’s queue size and the response time of the move message (as seen from the actors). From there on I was able to see those metrics in the Phoneix LiveDashboard. Since LiveDashboard only shows recent values, I also used the telemetry_metrics_statsd library to send the metrics to a local statsd server with graphite for visualization (using the graphiteapp/graphite-statsd docker image).

See the code

I started out with 20 actors. This worked fine, and I was seeing response times between 5 and 65ms. I then raised the count by 20 each time. Getting up to 60 went fine overall with occasional increases in queue size / response time. But, when I got up to 80, it took some time before after startup before the queue went down to zero. Going up a bit to 90 led to the queue rarely going down to zero and response times of between 250 and 450ms, which I considered to be around the breaking point.

Reducing The move Message Response Size

My first idea for allowing me to handle more simultaneous clients was to change my default map response from being a List-of-Lists to a Map.

Show me the code!

What this means is that, instead of the server returning this to clients:

[[nil, nil, :tree],

[:actor, nil, nil],

[:actor, :tree, nil]]

It would return this:

%{

{2, 0} => :tree,

{0, 1} => :actor,

{0, 2} => :actor,

{1, 2} => :tree

}

While that isn’t much sparser in those examples, my hope was that with a larger map section with trees and actors spread out that this would be less to send.

Unfortunately, it didn’t seem to actually help much. Thinking about this later, I realized one reason could be that I was starting all of the actors in the same place on the map, meaning that the “sparse” format wasn’t making much of a difference in the case that I was testing.

While this didn’t help, I still kept the change as I felt that it was a better solution and because I didn’t have any reason to think it would perform worse 😊

Sending Map Updates Asyncronously

The next thing that I tried was simply returning true when handling move messages but sending a map update to clients asyncronously. While this didn’t help with scaling, I was able to fix the above problem where players only see updates when they move. I also felt that it was a good way to setup the messages as it is the same way that LiveView works (incoming messages update the state and LiveView sends outgoing websocket messages to all clients whenever there is a need for them to know about state changes).

Reducing the Map Section Size Returned

My next experiment was to reduce the size of the map section which is returned to clients. Originally I returned a 27x27 section of the map which I reduced to a 17x17 section. This means that the number of potential squares returned is 289 instead of 729. This helped me have up to 130 actors at once, which was definitely a good jump! This was an easy change to make because I didn’t have a specific purpose for the game yet, but if this is an actual game that I wanted to release I would want to think as the “game designer” what map size is important. Overall, though, this would be much less important given the next thing that I tried…

Allow Clients to Ask For Map Updates

If we have, for example, 100 clients which are moving once every second and each client gets an update whenever another client moves, the game server will need to send around 10,000 messages every second! While the LiveView clients which connect to the game need to these map updates from the game server, the actor clients which are just moving randomly didn’t use that information. This means that we can avoid sending many of these messages! So my next idea: allow a client to specify if they want updates (or not) when they register.

Since there was already a register message that clients send on startup, I was easily able to add an options argument which can have a return_view_update key. By having actors specify that they didn’t want updates I was able to spin up 1,000 actors. Big progress!

Scale back the rate of updates

Increasing the number of actors by 770% is great, but even though our LiveView process is the only one receiving updates it is still getting 1,000 updates every second! A human eye only sees updates on the order of 60 frames per second. Fortunately it’s easy to use Process.send_after to have our game server send itself a message on a regular basis. Using this, I started with having the game server update clients around once every 200ms. This meant five frames per second.

This was a bit sluggish, but I realized that the most important thing is for a player to see their own updates quickly. If there is a 200-300ms delay between an actor moving and the player seeing it then probably players won’t notice. So, I simply send a message back to just the client every time they move (if they’ve set return_view_update). This means that they get an update as fast as possible without worrying about updating other clients immediately.

Overall this worked quite well, allowing me to have around 6000 actors at once! Since making updates to players now happens asyncronously this change was super easy!

Scaling Too High

I wrote above that I had scaled to around 6000 actors, but for a little while I was scaling up and up and up until I got to around 50,000 actors thinking that I had stumbled onto something amazing! It was then that my skepticism kicked in, and I realized I was just changing the number of trees generated on the board. When I thought I was able to handle 50,000 clients, it was really 50,000 trees. So, while not as useful, I guess at least I know I can have at least 50,000 trees in my fake game.

(Also, to be completely open: I end up making the above mistake one more time later on. 🤦♂️)

Time Out!

It was about this point that I was starting to see timeouts from the actors during startup. There are a couple of twists here, so I’ll try to lead you carefully along this path:

Since early in the development of the game server the actors have been started up in a handle_continue. The handle_continue callback exists to continue the work of the init callback, both of which are for running code when the process first starts up. During init, though, messages can’t arrive in the processes’ mailbox while they can during handle_continue. Since starting up actors isn’t critical to getting a game server running, I put the login inside of handle_continue

My worry was that the actor startup was taking too long. The default timeout for GenServer messages is 5000ms, so even if the mailbox can receive messages during the running of handle_continue, if handle_continue takes too long some messages may time out while waiting. If the message times out, then the actor crashes. Perhaps starting up more and more actors was keeping the game server from getting down to it’s job quickly enough?

What’s one thing to try in Elixir when you’ve got a problem? Create another process! 1 I thought to use a Task (specifically Task.Supervisor.async_nolink) to startup a temporary process which just has the job of starting up all of the actors.

That was maybe a good idea, in a way, but it didn’t actually help with the timeouts! After some tracing and debugging I found that it actually started up the actors quite quickly! It seemed that the register and move messages were just coming at the server so quickly at first that it struggled to keep up. After a certain number of clients, it couldn’t respond to messages within the 5000ms timeout.

So, ok, the timeout is just a default, so increase the timeout, right? That certainly works! But:

- Since it’s the default, I didn’t want to change it without a good reason

- If I change the timeout, I couldn’t compare my previous results to my future results

So, with increasing timeouts as a tool in my pocket, I moved on!

Trying Map.update!

Another small improvement I tried: Using Map.update instead of Map.update!. My thought was that Map.update was probably doing some sort of if check for the key. Perhaps without that and depending on an exception be raised/caught would improve things? That turned out to be very not true, and with the help of the benchee library I was able to see how they compared in cases where the key in question existed or not.

You can see the results of that benchmark in the snippets below. But, regardless of which version, I tried it didn’t make a difference to how many actors I could create. It was great to learn something about Elixir, but this was not a bottleneck.

See the code

move_and_update: A Very Specific Solution

I thought perhaps that the if check for return_view_update could be a place to improve. Perhaps instead of registering to request updates during registration, clients could send a move_and_update message instead of a move when they want an update afterward. It did seem to help a bit (allowing me to go from around 8,000 actors to around 9,000), but I didn’t really like the solution, so I decided the improvement wasn’t worth it. I like the simplicity of just having the move message overall. If using move_and_update made a big difference or if it helped me to meet the requirements of the application I’m building I would revisit this.

Having Actors Wait on Startup

I thought about how I could independently control:

- how long actors wait before sending their first message (via process startup)

- how long an actor waits between moves (via the repeating

handle_info)

Since I was still getting timesouts, I decided to try waiting 3000ms at startup while leaving the time between moves as 1000ms. It helped a bit: again allowing me to go from around 8,000 actors to around 9,000. Since I’m OK with the actors taking a bit more time to move, I left this one in.

A Discovery!

Then I came to a big discovery. During client registration the server was still sending back the map section as a response, even if the player hadn’t asked for updates! Since registration happens just once, while the move message happens a lot, this might not seem like a big deal. However, when the game tried to start up many, many actors, it is just the sort of thing that could cause it get behind in processing it’s queue and…. create timeouts!

So I simply had the response from register be a true. Then I could just call the same function that I already had to queue up a map update message for the client (if they’ve set return_view_update). With that change, I was then able to start up around 13,000 actors, making for a 44% increase!

A Step Backward

I was pretty sure that this wouldn’t make things better, but it turned out to make things much worse:

I tried putting the logic of sending map updates during register or move in a handle_continue. This is for code which executes after a message is handled, just like after init. This didn’t allow me to scale any more, but it also had the effect that responsiveness to player moves were slower, especially when the game server had high queue lengths.

Maybe using “continue” meant the server sending a message to itself and that the message goes to back of the queue? That would mean that the map update message had to wait to be sent instead of being sent right away. I’m not 100% sure about this though. When “continue” is used during init of a GenServer it is guarunteed to be processed before other messages, but when it’s used in a handle_call where other messages have already been queued up that may not be the same

Anyway, I removed that change :)

Sleep to Scale

Even with the reduction in work when handling register messages, I would still, at some point, get timeouts. I thought perhaps that if I put a delay (say 10ms) between startup of each of my actors I could avoid that or at least push it back further. This stretches out the time it would take to start up all of the actors to at least a couple of minutes. If I were still doing the work directly in the handle_continue this would be a problem as the game server wouldn’t be able to respond to messages during that time. Fortunately I was still using Task.Supervisor.async_nolink so the the game server gets down to handling messages just as soon as it’s handed off the task of starting up actors to the Task.

Overall it helped some! I was able to startup around 15,000 actors and the server was pretty stable and responsive (though at that point the queue generally wasn’t getting worked down and move response time can be between 1000 and 2000ms). But as an unexpected benefit: by starting up the actors slowly I was able to more easily see the point at which the metrics show things becoming unstable.

Other Notes / Learnings

Visualizing Possibilites

I found it fascinating to watch the actors spread out from a single point. Since the actors move randomly one space at a time, the most likely thing for them to do would be to stay in one spot. If I spawned 1,000 actors then I could see some making it out of the central mass, giving a viseral sense of how far actors could go in the rare cases. It’s was a sort-of live 2D histogram of potential end positions after X number of moves.

LiveDashboard

LiveDashboard and telemetry were amazing for getting up-and-running very quickly, but it was sometimes frustrating to only see the recent values. Also, sometimes when I would refresh the metrics would change dramatically, giving me the feeling that something wasn’t updating correctly. Sending the metrics to statsd/graphite was slower and had less resolution, but felt more reliable. I’m super glad that telemetry allows for both options (and more) to exist!

Other Potential Improvements

At this point I had made a lot of progress and learned a lot of things. If I would actually want to use this for a real project, there are some other things that I could investigate improving:

Using an ETS Table

If I used an ETS table that only the game server writes to, it could allow client processes to retrieve a map state by querying the table. This could reduce the load of the game server and maybe allowing for better scaling.

Reducing Actor Movements

If the actors moved less often then the game server would have fewer messages / second, allowing it to support more clients at once. Having actors wait a random amount of time between movements could preserve a feeling of realism for the player.

Potential Challenges for Building a Game

I also have some ideas for what I might do to actually turn this into a real game (at least something which people might want to play for a bit as a demo)

Testing Real Player Load

I’ve pushed the limit for how many actors which can be run at once, but they don’t need the map updates. Adding (or simulating) many real players would be different and might require a strategy like having an ETS table.

Enforcing Game Rules

There will probably be a need to implement some game rules. For a start I might implement a rule like “players/actors cannot be in the same spot as a tree”.

Other Kinds of Actors

While having just one kind of actor made benchmarking straightforward, it would be great to make the world more interesting by adding other kinds of actors. One example I can imagine would be bacteria emoji which grow and die with rules similar to Conway’s Game of Life.